ARPANET what does sputnik have to do with the internet

This essay is the last of a four-part serial, which commemorates the anniversary of the beginning ever message sent across the ARPANET, the progenitor of the Internet on October 29, 1969.

In today's hyper-tech earth, virtually whatsoever new device (even a fridge, let solitary phones or computers) is born "smart" enough to connect easily with the global network. This is possible considering at the core of this worldwide infrastructure we call the Internet is a set of shared communication standards, procedures and formats called protocols. Notwithstanding, when in the early 1970s, the first four-nodes of the ARPANET became fully functional things were a fleck more complicated. Exchanging data betwixt dissimilar computers (let alone different figurer networks) was not equally easy as information technology is today. Finally, there was a reliable packet-switching network to connect to, simply no universal linguistic communication to communicate through information technology. Each host, in fact, had a set of specific protocols and to login users were required to know the host'southward own 'linguistic communication'. Using ARPANET was like existence given a phone and unlimited credit simply to find out that the simply users we can telephone call don't speak our linguistic communication.

Predictably, the new network was scarcely used at the beginning. Excluding, in fact, the small circle of people directly involved in the project, a much larger crowd of potential users (e.g. graduate students, researchers and the many more than who might have benefited from information technology) seemed wholly uninterested in using the ARPANET. The just thing that kept the network going in those early months was people irresolute jobs. In face, when researchers relocated to one of the other network sites – for instance from UCLA to Stanford – then, and simply so, the usage of those sites' resources increased. The reason was quite unproblematic: the providential migrants brought the gift cognition with them. They knew the procedures in use in the other site, and hence they knew how to "talk" with the host computer in their old department.

To detect a solution to this frustrating problem, Roberts and his staff established a specific group of researchers – nigh of them still graduate students – to develop the host-to-host software. The group was initially called the Network Working Group (NWG) and was led by a UCLA graduate educatee, Steve Crocker. Later, in 1972, the group changed its name in International Network Working Group (INWG) and the leadership passed from Crocker to Vint Cerf. In the words of Crocker:

The Network Working Group consists of interested people from existing or potential ARPA network sites. Membership is not closed. The [NWG] is concerned with the HOST software, the strategies for using the network, and initial feel with the network.

The NWG was a special body (the first of its kind) concerned not merely with monitoring and questioning the network'due south technical aspects, simply, more broadly, with every aspect of information technology, fifty-fifty the moral or philosophical ones. Cheers to Crocker'southward imaginative leadership, the discussion in the grouping was facilitated past a highly original, and rather autonomous method, still in employ five decades later. To communicate with the whole group, all a member needed to exercise was to send a simple Request for Annotate (RFC). To avoid stepping on someone's toes, the notes were to be considered "unofficial" and with "no status". Membership to the grouping was not closed and "notes may be produced at any site by everyone". The minimum length of a RFC was, and still is "one sentence".

The openness of the RFC process helped encourage participation among the members of a very heterogeneous group of people, ranging from graduate students to professors and plan managers. Following a "spirit of unrestrained participation in working group meetings", the RFC method proved to exist a critical asset for the people involved in the project. It helped them reflect openly most the aims and goals of the network, within and across its technical infrastructure.

The significance of both the RFC method and the NWG goes far across the critical part they played in setting upward the standards for today'due south Internet. Both helped shape and strengthen a new revolutionary culture that in the proper noun of cognition and problem-solving tends to condone power hierarchies every bit nuisances, while highlighting networking every bit the only path to find the all-time solution to a trouble, any problem. Within this kind of environs, it is not one's particular vision or idea that counts, merely the welfare of the environment itself: that is, the network.

This particular culture informs the whole communication milky way we phone call today the Internet; in fact, information technology is one of its defining elements. The offspring of the marriage between the RFC and the NGW are called web-logs, web forums, email lists, and of course social media while Internet-working is now a cardinal-aspect in many processes of human interaction, ranging from solving technical problems, to finding solution to more than complex social or political matters.

Widening the network

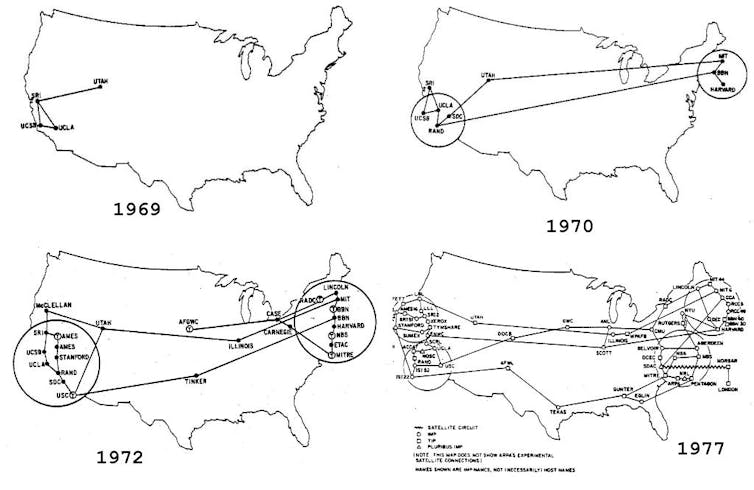

The NWG however needed almost 2 years to write the software, simply eventually, by 1970 the ARPANET had its first host-to-host protocol, the Network Control Protocol (NCP). By December 1970 the original 4-node network had expanded to 10 nodes and 19 hosts computers. Four months later, the ARPANET had grown to 15 nodes and 23 hosts.

By this time, despite delivering "data packets" for more than a twelvemonth, the ARPANET showed almost no sign of "useful interactions that were taking place on [it]". The hosts were plugged in, simply they all lacked the right configuration (or knowledge) to properly apply the network. To make "the globe take notice of bundle switching", Roberts and his colleagues decided to requite a public demonstration of the ARPANET and its potentials at the International Conference on Computer Communication (ICCC) held in Washington, D.C., in October 1972.

The demonstration was a success: "[i]t really marked a major change in the mental attitude towards the reality of packet switching" said Robert Kahn. It involved – among other things – demonstrating how tools for network measurement worked, displaying the IMPs network traffic, editing text at a altitude, file transfers, and remote logins.

Information technology was just a remarkable panoply of online services, all in that i room with about fifty dissimilar terminals.

The demonstration fully succeeded in showing how bundle-switching worked to people that were not involved in the original project. It inspired others to follow the example set by Larry Roberts' network. International nodes located in England and Kingdom of norway were added in 1973; and in the following years, others bundle-switching networks, independent from ARPANET, appeared worldwide. This passage from a relatively small experimental network to i (in principle) encompassing the whole world confronted the ARPANET'south designers with a new claiming: how to make different networks, that used different technologies and approaches, able to communicate with each other?

The concept of "Internetting", or "open-compages networking", first introduced in 1972, illustrates the disquisitional need for the network to expand across its express restricted circle of host computers.

The existing Network Control Protocol (NCP) didn't meet the requirements. Information technology had been designed to manage communication host-to-host within the same network. To build a truthful open reliable and dynamic network of networks what was needed was a new full general protocol. It took several years, but eventually, past 1978, Robert Kahn and Vint Cerf (two of the BBN guys) succeeded in designing it. They called information technology Transfer Control Protocol/Cyberspace Protocol (TCP/IP). Every bit Cerf explained

'the job of the TCP is merely to take a stream of messages produced by ane HOST and reproduce the stream at a strange receiving HOST without change.'

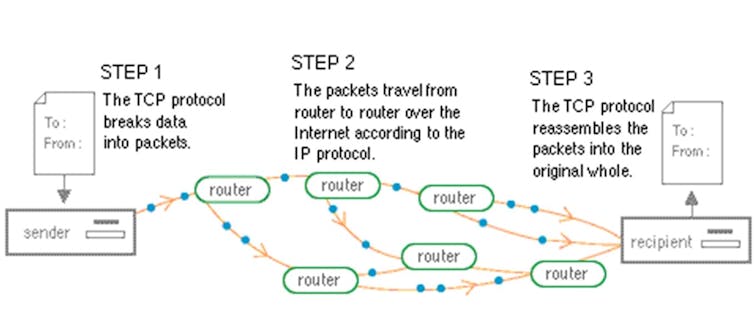

To requite an example: when a user sends or retrieve information across the Internet – e.one thousand., access Web pages or upload files to a server - the TCP on the sender's machine breaks the message into packets and send them out. The IP is instead the function of the protocol concerned with "the addressing and forwarding" of those individual packets. The IP is a disquisitional part of our daily Cyberspace feel: without information technology, information technology would be practically incommunicable to locate the data we are looking for amidst the billions of machines connected to the network today.

On the receiving finish, the TCP helps reassemble all the packets into the original messages, checking errors and sequence lodge. Thanks to TCP/IP the commutation of data packets between different and afar networks was finally possible

Cerf and Khan'south new protocol opened upward new possible avenues of collaboration betwixt the ARPANET and all the other networks around the world that had been inspired by ARPA's work. The foundations for a worldwide network were laid, and the doors were wide open for anyone to bring together in.

Expansion of the ARPANET

In the years that followed, the ARPANET consolidated and expanded, all while remaining almost unknown to the general public. On July one, 1975, the network was placed under the direct command of the Defense Communication Bureau (DCA). Past then there were already 57 nodes in the network. The larger information technology grew, the more than hard it was to make up one's mind who was actually using it. There were, in fact, no tools to cheque the network users' action. The DCA began to worry. The mix of fast growth charge per unit and lack of command could potentially go a serious issue for national security. The DCA, trying to control the situation, issued a series of warnings confronting whatsoever unauthorised admission and use of the network. In his last newsletter before retiring to civilian life, the DCA'southward appointed ARPANET Network Manager, Major Joseph Haughney wrote:

Just armed services personnel or ARPANET sponsor-validated persons working on government contracts or grants may apply the ARPANET. […] Files should not be [exchanged] by anyone unless they are files that accept been announced equally ARPANET-public or unless permission has been obtained from the owner. Public files on the ARPANET are not to be considered public files outside of the ARPANET, and should not be transferred, or their contents given or sold to the full general public without permission of DCA or the ARPANET sponsors.

Withal, these warnings were largely ignored every bit near of the networked nodes had, Haughney put information technology, "weak or nonexistent host access to the control mechanism". By the early 1980s, the network was essentially an open access area for both authorised and non-authorised users. This state of affairs was made worse by the desperate drop in computer prices. With the potential number of machines capable of connecting to the network increasing constantly, the concern over its vulnerability rose to new heights.

The 1983 hit movie, State of war Games, about a young calculator whiz who manages to connect to the super computer at NORAD and virtually outset World Discussion III from his bedroom, perfectly captured the mood of the militaries towards the network. By the terminate of that year, the Department of Defense 'in its biggest step to date confronting illegal penetration of computers' – as The New York Times reported – "dissever a global figurer network into split up parts for military and civilian users, thereby limiting admission past university- based researchers, trespassers and possibly spies".

The ARPANET was effectively divided in 2 distinct networks: i withal chosen ARPANET, mainly defended to inquiry, and the other chosen MILNET, a military operational network, protected by strong security measures like encryption and restricted access command.

By the mid 1980s the network was widely used by researchers and developers. Only it was likewise existence picked up past a growing number of other communities and networks. The transition towards a privatised Internet took ten more years, and it was largely handled past the National Science Foundation (NSF). The NSF's own network NFTNET had started using the ARPANET equally its backbone since 1984, just by 1988 the NSF had already initiated the commercialisation and privatisation of the Internet by promoting the development of "individual" and "long-booty networks". The role of these individual networks was to build new or maintain existing local/regional networks, while providing admission to their users to the whole Net.

The ARPANET was officially decommissioned in 1990, whilst in 1995 the NFTNET was shut down and the Internet effectively privatised. By and then, the network - no longer the individual enclave of reckoner scientists or militaries - had become the Internet, a new galaxy of advice set to be fully explored and populated.

The Net

During its early on stages, betwixt the 60s and 70s, the communication milky way spawned by the ARPANET was not but mostly uncharted space, but, compared to today' standards, also mainly empty. It continued as such well into the 90s, before the technology pioneered with the ARPANET projection became the backbone of the Cyberspace.

In 1992, during its start phase of popularisation, the global networks connected to the Internet exchanged almost 100 Gigabytes (GB) of traffic per day. Since so, data traffic has grown exponentially along with the number of users and the network's popularity. A decade afterwards, thanks to Tim Berners Lee's Globe Wide Spider web (1989), there is an always increasing availability of cheap and powerful tools to navigate the milky way, non to mention the explosion of social media from 2005 onward. Then, 'per day' became 'per 2nd', and in 2014 global Internet traffic peaked at 16,000 GBps, with experts forecasting the number to quadruple before the decade is out.

Even so, numbers tin sometimes be deceptive, equally well every bit frustratingly confusing for the non-expert reader. What hides beneath their dry technicality is a simple fact: the indelible impact of that get-go stuttered how-do-you-do at UCLA on October 29, 1969 has dramatically transcended the apparent technical triviality of making 2 computers talk to each other. Nearly 5 decades after Kleinrock and Kline'south experiment in California, the Cyberspace has arguably become a driving force in the daily routines of more than than three billion people worldwide. For a growing number of users, a mere minute of life on the Internet is to be part, simultaneously, of an endless stream of shared experiences that include, amidst other things, watching over 165,000 hours of video, being exposed to x one thousand thousand adverts, playing most 32,000 hours of music and sending and receiving over 200 million emails.

Albeit at different levels of participation, the lives of about half of the world population are increasingly shaped by this expanding communication galaxy.

We use the global network most for everything. 'I'm on the Internet', 'Check the Internet', 'It's on the Internet' and other similar stock phrases have become portmanteau for an increasing range of activities: from chatting with friends to looking for love; from going on shopping sprees to studying for a University degree; from playing a game to earning a living; from becoming a sinner to connecting with God; from robbing a stranger to stalking a erstwhile lover; the listing is virtually endless.

Merely in that location is much more than than this. The expansion of the Cyberspace is deeply entangled with the sphere of politics. The more people encompass this new historic period of communicative affluence, the more than it affects the way in which we exercise our political will in this world. Barack Obama's victory in 2008, the Indignados in Spain in 2011, the Five Star Movement in Italy in 2013, Julian Assange'southward Wikileaks and Edward Snowden'due south revelations of the NSA'south hole-and-corner system of surveillance are but a handful of examples that show how, in simply the terminal decade, the Internet has changed the way in which we engage with politics and challenge power. The Snowden'due south files, however, also highlight the other, much darker side of the story: the more we get networked, the more than we become obliviously exploitable, searchable, and monitored.

Several decades afterward the journeying began, we have yet to reach the full potential of the 'Intergalactic Network' imagined by Licklider in the early 1960s. However, the quasi-perfect symbiosis betwixt humans and computers that we experience every day, albeit not without shadows, it is arguably ane of humanity's greatest accomplishments.

Source: https://theconversation.com/how-the-internet-was-born-from-the-arpanet-to-the-internet-68072

0 Response to "ARPANET what does sputnik have to do with the internet"

Post a Comment